“Am I making money?”

“Am I making money?”

Every smart entrepreneur asks this question. With such simple question, you’d think there’d be a simple answer — but a long line of failed businesses suggests otherwise. So why the confusion? And how should smart entrepreneurs be evaluating their business’ performance?

The Confusion

The confusion arises from the multiple ways to arrange numbers. Arranged one way, and you have “taxable income” reportable to the government. Arranged another, you’ve got “net income” according to generally accepted accounting principles. Arranged yet a third, and you’ve got the change in your bank balance since last year. Yet a fourth and fifth, and there’s “EBITDA” and “ROI”. And the list goes on. The upshot of all these approaches: “making money” has far from a universal definition, and sometimes will even contradict each other. What’s an entrepreneur to do?

For the business owners we advise, we recommend two lenses to keep eyes on the big picture: cash flow and profit.

- At the end of the day, it’s cash flow in the bank that gives you freedom to pursue opportunities. And conversely, it’s lack of cash that’s going to keep you restricted, or even pulled under.

- But cash comes from realized profit: which we define as consuming less economic value than you create. Profit reflects expectations and understandings in an attempt to match sales with their corresponding costs, regardless of whether cash changes hands at the time.

What do I mean? Let’s a take a look at two examples and what we call their ‘cash profiles’ and ‘profit profiles’.

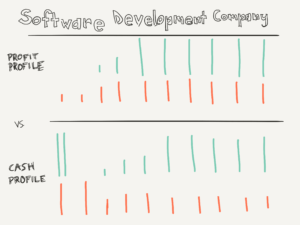

Profit vs. Cash Profiles: Software Development Company

Pretend for a moment you’re a software development company. Your “profit profile” is the visual pattern of sales and costs you experience in the process of creating a profit. For example, you may spend two years writing and testing code, which’ll be treated as building an intellectual asset. Then once your software is released, you might experience eight years of sales, accompanied by typical operational costs such as marketing and support, plus the using up of the intellectual asset. To answer the question, “are we making money?”, you really have to take all ten years into view to make the judgement.

This pattern forms your “profit profile”, but your “cash profile” will look very different. Cash profiles aren’t concerned with matching sales and corresponding costs across the timeline (such as the software asset above) – it just wants to know when cash is coming in, and when it’s going out. So in our example, venture capital provided the initial cash infusion that funded the first two years of development. Then in year three, cash from sales starts to ramp up and eventually levels off, accompanied by marketing and support costs. From a pure cash standpoint, the question of “are we making money?” will be very different in year 1, year 3, and year 6.

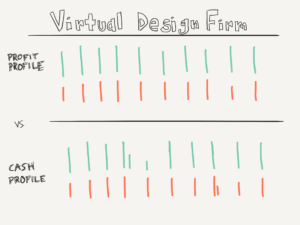

Profit vs. Cash Profiles: Virtual Design Firm

Now let’s take a look at a different example: pretend you’re a virtual design firm instead. Your “profit profile” is comprised of a mix of one-off projects and recurring customer work, offset primarily by fixed compensation and a smidge of technology costs. Since your profit profile doesn’t shift large sales or expenses to different points on the timeline (like the software asset), getting a handle on your economic profit is much simpler: all other things being equal, a 12-month window should provide a clear picture.

But no so fast: your “cash profile” may provide some exceptions. For example, perhaps you land a large annual contract right at the end of the year with a customer who paid upfront. You’ll have a significant cash inflow, but it won’t be show up as “sales” until it’s actually delivered over the course of next year. Separately, maybe you just paid off a line of credit balance recently – that’s a large cash outflow that’ll have essentially have no impact on the “profit” calculation.

So Am I Making Money?

Weaving these examples together, we can start to see how things can go horribly wrong:

- If you’re just looking at your profit, you can easily miss the reality of the cash movements going on underneath the surface, which can literally result in a large profit with no money to pay the taxes on it. (We’ve seen this happen many times, and the owner often uses the following year’s cash to pay the tax, further distorting the picture.)

- Conversely, if you’re only looking at the cash flow and not minding your profit profile, you could see a high bank balance and think you’re doing swell, not realizing that the asset whose value you’ve been using up the last few years has run its course and is going to require a large cash outlay to replace, thereby putting you in the red. (Seen this one too, and the business just close up shop or go into unnecessary debt to make up the difference.)

So what’s the answer to the question “Am I making money?” — It’s really a synthesis of both:

You want to evaluate if expenses are less than sales over the profit cycle, *and* that cash outflows never get ahead of inflows during that same cycle.

If one or the other aren’t true, you aren’t making money, no matter what the paper might say. And when both are true, you’ve got yourself a winner. By looking through the eyes of both profit and cash, you avoid the distortions of relying on one alone, and get a true 3D picture of your business’ economic performance.

(Postscript: Without a proper financial design and system in place, this can be down right impossible to get an accurate read of. But aided by good design and financial automation, it’s so much easier to look both backwards and forwards to make sure your financial model is working.)